When was the wheel invented? Most history books will tell you the Sumerians created the first wheel in Mesopotamia around 3500 BCE. That story just got a lot more interesting. New archeological discoveries are rewriting what we thought we knew about one of humanity's most crucial inventions.

The oldest surviving wooden wheel actually dates to the Copper Age around 3130 BCE. Even more surprising, some researchers now believe copper miners in the Carpathian Mountains may have developed wheels up to 6,000 years ago. These findings challenge everything we've accepted about where and when the wheel first appeared.

Here's what makes this story fascinating: while historians long credited Mesopotamian Sumerians with inserting rotating axles into solid wooden disks, archeologists keep finding wheel evidence across Europe, Asia, and Northern Africa from the same time period. We're talking about the Copper Age, roughly 5000 to 3000 BCE. The discovery of over 150 miniaturized wagons in the Carpathian region alone suggests multiple civilizations developed wheels independently.

What you'll discover in this guide goes far beyond the traditional Mesopotamia-first narrative. These findings reveal a much more complex picture of how ancient peoples solved the challenge of moving heavy loads—and why the wheel's true origins may surprise you.

Image Source: History Cooperative

Understanding the wheel's true origins requires examining evidence from multiple ancient civilizations. What archeologists have discovered challenges the single-origin theory that dominated historical thinking for decades. The evidence points to parallel development across several regions during roughly the same time period.

The Mesopotamian story begins with clay tablet pictographs discovered in the Eanna district of Uruk. These Sumerian artifacts date to approximately 3500-3350 BCE and show clear depictions of wheeled wagons. The pictographic signs feature illustrations of sledge-like vehicles with two round impressions underneath—what scholars interpret as wheels.

This evidence doesn't establish Mesopotamia as the definitive birthplace of the wheel. Comparable evidence from other regions appears during the same period, suggesting ancient peoples may have developed similar solutions independently.

The most significant early wheel evidence comes from southern Poland. The Bronocice pot, attributed to the Funnelbeaker culture, contains what many archeologists consider the oldest well-dated representation of wheeled vehicles in the world. Radiocarbon testing dates this ceramic vase to 3635-3370 BCE—potentially predating the Mesopotamian evidence.

The pot features five wagon illustrations, each showing a shaft for a draft animal and four wheels. This suggests functioning wagons existed in Central Europe during the 4th millennium BCE. The detail level indicates these weren't just conceptual drawings but representations of actual vehicles.

Eastern Europe's Cucuteni–Trypillia culture has yielded objects that may be potter's wheels from the mid-5th millennium BCE—potentially several hundred years before similar Mesopotamian wheels. This culture also produced miniature wheeled models that predate any known Mesopotamian wheeled vehicle evidence.

The ancient Indus Valley civilization adds another layer to this story. Sites at Dholavira, Mohenjo-daro, and Harappa have revealed diverse toy wheels with various design features. These include disk-shaped, plano-convex, and biconvex wheels with both single and double hubs. Many terracotta figurines found at these sites were clearly toys, including small animal carts.

The evidence from these diverse regions appears during roughly the same historical period, making it difficult to determine which culture first invented the wheel. Rather than a single breakthrough, the wheel appears to represent multiple ancient peoples solving similar transportation challenges.

Image Source: Ancient Origins

Wheel technology didn't stay static after its invention. Over 2,500 years, ancient engineers transformed simple wooden disks into sophisticated mechanical systems that would dominate transportation until the industrial revolution.

The earliest wheels started as solid wooden disks during the late Neolithic period, appearing alongside other technological advances that marked the early Bronze Age. We can see this craftsmanship in the Ljubljana Marshes Wheel from Slovenia, dating to approximately 3150 BCE. This remarkable artifact shows two ash planks joined with tongue and groove construction, reinforced with precisely placed ash battens.

The specifications tell the story: a 72-centimeter diameter wheel connected to a 124-centimeter-long oak axle, demonstrating sophisticated woodworking techniques for the era. The wheel-axle combination rotated as a single unit, secured with oak wedges. Before these fixed wheels, ancient peoples relied on "free rollers"—logs placed under heavy objects to ease movement.

Around 2000 BCE, the Sintashta culture revolutionized wheel design with the invention of spoked wheels. This Bronze Age society in the Don-Volga interfluve developed chariot technology that would change ancient warfare forever. Their earliest known chariots, found exclusively in Sintashta burials, featured wheels with 10-12 spokes measuring approximately 130-160 centimeters between wheels.

This innovation created nimbler, lighter vehicles perfect for combat maneuvers. The spoked design reduced weight while maintaining strength—a principle that continues to influence modern wheel engineering. For those interested in how these ancient designs evolved into today's technology, visit Performance Plus Tire's wheel collection.

Celtic chariots marked the final major pre-modern wheel advancement during the first millennium BCE with iron rims around wooden wheels. Made from sturdy ash wood with one-piece, iron-rimmed wheels, these chariots represented peak ancient wheel engineering. The iron rim provided exceptional durability and strength, protecting the wooden structure while improving performance on rough terrain.

Celtic innovation also positioned wheels beyond the chariot's body edge, offering greater stability and improved cornering. This progression from solid wooden disks to iron-reinforced spoked wheels established the foundation for all subsequent wheeled transportation developments.

The evolution spans roughly 2,500 years of continuous improvement, with each advancement solving specific problems while creating new possibilities for human mobility and commerce.

Image Source: Britannica

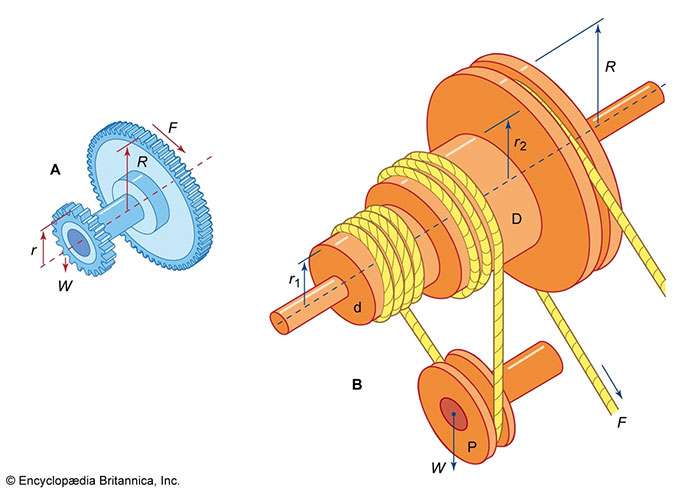

Understanding why wheels work requires looking beyond the artifacts themselves. The wheel's success comes from basic physics principles that ancient civilizations discovered through trial and practical necessity.

The wheel and axle operates as a simple machine that converts rotational motion into forward movement. This system connects two disks of different diameters that rotate together around the same axis. The mechanical advantage depends directly on the ratio between the wheel's radius and the axle's radius—larger wheels provide greater mechanical advantage. Ancient peoples used this principle to multiply force by changing the distance over which it was applied, making heavy loads manageable with less effort.

Wheels solve a fundamental problem: moving heavy objects efficiently. A wheeled vehicle requires significantly less work to move than dragging the same weight. The physics are straightforward—rolling resistance is approximately 40 times less than sliding friction. Early wheels transferred friction from the ground to the axle, where surfaces interact with minimal resistance. Ancient Egyptians understood this principle well, using rollers to move heavy objects along the ground before developing fixed wheel systems.

Wheels evolved from simple rollers—loose cylinders or tree trunks arranged side-by-side. Before proper wheel bearings existed, ancient vehicles used thru-axle or trunnion systems that allowed wheels to turn but created significant friction. These systems used solid wooden spindles passing through wheel centers, supported by the vehicle's frame. Over time, these primitive axles evolved into the wheel-axle combination we recognize today. Modern wheel technology continues this evolution—explore diverse wheel designs at Performance Plus Tire's wheel collection.

The wheel's story extends far beyond mechanical innovation. Different civilizations adopted wheel technology based on their unique needs, geography, and cultural values. Some cultures embraced it wholeheartedly, others adapted it selectively, and a few understood the principles but chose different paths entirely.

Northern China's Longshan culture developed some of the most advanced pottery wheels between 2500-2000 BCE. These fast-spinning wheels enabled artisans to create exceptionally refined ceramics, including their famous "eggshell pottery" with walls so thin they seem almost transparent.

Longshan potters achieved remarkable sophistication in their craft. They created elegant goblets with flared brims, cups, and stems in multiple shapes. Their most impressive technique involved throwing vessels in three separate sections, then joining them together and adding pierced decorations. The culture's wheel mastery also facilitated the production of highly polished black pottery through specialized firing methods using reduced oxygen environments.

Here's something fascinating: Mesoamerican civilizations clearly understood wheel mechanics but never used wheels for transportation. Archeologists have discovered approximately 100 wheeled figurines across Veracruz, Michoacan, Guerrero, and El Salvador. These toys typically depict animals—mostly dogs and jaguars—with axles threaded through leg loops and wheels on each end. Many larger examples even functioned as flutes or whistles.

The absence of wheeled transport wasn't due to ignorance. Geographic challenges, lack of suitable draft animals, and possibly religious beliefs that valued physical labor as spiritual practice all contributed to this cultural choice. Sometimes understanding a technology and choosing not to adopt it reveals as much about a civilization as embracing it does.

Asian cultures elevated the wheel beyond practical tool to profound symbol. India's oldest spoked wheel evidence appears in Mesolithic cave paintings from Mirzapur. The chakra (wheel) became central to Hindu cosmology, representing time and seasons as Rtachakra. Buddhist tradition adopted the dharmachakra (wheel of law) to symbolize Buddha's teachings.

Most recognizably, the wheel features prominently in India's national identity. From Emperor Ashoka's adoption of the chakra to Gandhi's association with the charkha (spinning wheel), this symbol became powerfully linked to India's freedom struggle and self-reliance. The spinning wheel represented both practical independence and spiritual discipline—showing how ancient technology could embody modern political ideals.

New archeological evidence has shattered the old story about wheel origins. What we thought we knew about Mesopotamia being first? That's just one piece of a much bigger puzzle. The Bronocice pot from Poland, those Cucuteni–Trypillia miniature wheels, and discoveries across the Indus Valley prove multiple civilizations developed wheels independently during the Copper Age.

The wheel's journey from solid wooden disks to spoked designs to iron-rimmed Celtic wheels took about 2,500 years. That evolution set the stage for every wheeled vehicle until the industrial revolution. The mechanical breakthrough was simple but game-changing—reducing friction by 40 times compared to dragging loads made heavy transport manageable for ancient societies.

Different cultures adopted wheels based on their specific needs and values. China's Longshan culture mastered pottery wheels for creating sophisticated ceramics. Mesoamerican societies understood the principles but never used wheels for transportation. The wheel became deeply symbolic across Asian cultures, representing everything from cosmic order to political identity.

Here's what makes this story remarkable: human innovation doesn't follow neat, linear paths. Ancient peoples faced similar challenges and often developed similar solutions independently. The wheel proves that breakthrough technologies can emerge simultaneously across different regions when the need exists.

Understanding these origins matters because the wheel remains central to modern civilization. From the custom wheels and tires we use today to the industrial machinery that powers our economy, this ancient invention continues to be humanity's most enduring and universal technological achievement. The story of how it really began shows us that innovation has always been a global, collaborative human endeavor.

Recent archeological discoveries are revolutionizing our understanding of when and where the wheel was invented, revealing a far more complex origin story than previously believed.

• The wheel wasn't invented in one place—evidence shows parallel development across Europe, Asia, and Africa during the Copper Age (5000-3000 BCE)

• The Bronocice pot from Poland (3635-3370 BCE) may contain the world's oldest wheel depictions, predating Mesopotamian evidence

• Wheel technology evolved over 2,500 years from solid wooden disks to spoked wheels to iron-rimmed Celtic designs

• The wheel's mechanical advantage reduces friction by 40 times compared to dragging, making it humanity's most transformative simple machine

• Different cultures adopted wheels selectively—China mastered pottery wheels while Mesoamericans understood the concept but never used it for transportation

This groundbreaking research demonstrates that human innovation often develops independently across civilizations, challenging our assumptions about technological progress and reminding us that even our most fundamental inventions have surprisingly complex origins.

The exact date of the wheel's invention is uncertain, but archeological evidence suggests it emerged during the Copper Age, around 3500-3000 BCE. The oldest known wooden wheel dates back to approximately 3130 BCE.

Rather than a single origin point, evidence indicates parallel development of the wheel across several ancient civilizations in Europe, Asia, and Northern Africa during the Copper Age.

Early wheels were solid wooden disks, which later evolved into spoked designs. The first wheels were likely used for pottery before being adapted for transportation. Modern wheels use advanced materials and have sophisticated designs for improved performance.

The wheel dramatically reduced friction in transportation, making it easier to move heavy loads. It also became a fundamental component in various machines and tools, revolutionizing agriculture, commerce, and warfare in ancient societies.

No, not all ancient civilizations adopted wheels for transportation. For example, the Inca built an extensive road network without using wheeled vehicles, while some Mesoamerican cultures had wheeled toys but didn't use wheels for practical purposes.